Cover by Hart Hallos

November Masthead

Editor-in-Chief | Sona Wink, BC’25

Managing Editor | Anouk Jouffret, BC’24

Deputy Editor | Victor Omojola, CC’24

Publisher | Jazmyn Wang, CC’25

Illustrations Editor | Oonagh Mockler, BC’25

Co-Layout Editors | Annie Poole, BC’24 & Siri Storstein, CC’26

Literary Editor | Miska Lewis, BC’24

Digital Editor | Jorja Garcia, CC’26

Senior Editors

Andrea Contreras, CC ’24

Josh Kazali, CC’25

Becky Miller, BC’24

Claire Shang, CC’24

Muni Suleiman, CC’24

Tara Zia, CC’26

Anna Patchefsky, CC’25

Iris Chen, CC’24

Staff Writers

Sagar Castleman, CC’26

Schuyler Daffey, CC’26

Amogh Dimri, CC’24

Jake Goidell, CC’24

Madison Hu, GS’24

Shreya Khullar, CC’26

Molly Leahy, BC’24

Molly Murch, BC’24

Sofia Pirri, CC’24

Dominic Wiharso, CC’25

Eva Spier, BC’27

Lucia Dec-Prat, CC’27

Maya Lerman, CC’27

Michael Onwutalu, CC’27

George Murphy, CC’27

Ava Lozner, CC’27

Chris Brown, CC’26

Eli Baum, CC’26

Owen Terry, CC’26

Vivien Sweet, GS’25

Gracie Moran, CC’25

Em Chmiel, CC’25

Alice Tecotzky, CC’24

Sam Hosmer, CC’24

Staff Illustrators

Emma Chen, CC’26

Cadence Gonzales, BC’26

Hart Hallos, CC’24

Maca Hepp, CC’24

Alexandra Lopez-Carretero, CC’25

Nayeon Park, CC’26

Amelie Scheil, BC’25

Betel Tadesse, CC’25

Phoebe Wagoner, CC’25

Fin Sterner, BC’25

Oliver Rice, CC’25

Emma Finkelstein, BC’27

Selin Ho, CC’27

Kendra Mosenson, BC’24

Justin Chen, CC’26

Isabelle Oh, BC’27

Jacqueline Subkhanberdina, BC’27

Table of Contents

Letter From the Editor

Blue Notes

Altruism, Butchered by Vivien Sweet

The Perils of Place by Michael Onwutalu

Long-Term Parking by Sam Hosmer

Campus Characters

Samara Huckvale by Muni Suleiman

Essay

Ousmane and I by Victor Omojola

Centerfold by Hart Hallos

Measure for Measure

Selected Poems by Sofia Whetstone

Selected Poems by Thaleia Dasberg

At Two Swords’ Length

Did You Pass the Background Check? by Amogh Dimri and Molly Leahy

Features

Nuss and Them by Sagar Castleman

Barnard Reproductive Health by Miska Lewis

Measure for Measure

Selected Poems by Sofia Whetstone

Selected Poems by Thaleia Dasberg

The Conversation

Letter From the Editor

A professor of mine once referred to the writers he loves most as “traveling companions” who he has kept alongside him throughout the decades. The phrase rings true to experiences I’ve had with particularly epic texts on class syllabi: The perspective of an author resonates and comes alive when their prose is fluid and filled with life, and when an idea is articulated with icy,

threadbare precision. This sort of reading can feel like discovering a lifelong companion and mentor.

Yet, sadly, being a history major means that most all of my traveling companions are long-dead. My connection with them is imaginary and one-sided, confined to my scribbles in the margins of their books.

Editing, which I do a fair deal of for this magazine, offers an alternative to my parasocial book-reading. While a lot of the job involves catching minor grammatical errors, it crucially requires the same sort of close-reading I do for coursework. Indeed, before I can suggest how to make a perspective clearer, I must first identify exactly what the author’s perspective is. Unlike the texts I read for class, however, when I annotate and scrawl questions in the margins of an article, the author, a Blue and White staff writer, responds and leaves questions of their own.

The November issue sees our writers find communion beyond the Google Doc, forging unexpected connections with people throughout Morningside Heights. Amogh Dimri runs into a high school friend while donning a full-body chicken costume, and, needless to say, a night of drunken revelry ensues. Sam Hosmer immerses himself within a digital network of library retirees as he digs for information about a sealed-off Kent elevator. Muni Suleiman and Sofia Pirri both reconnect with freshman year friends to discuss their projects and future ventures, which range from a documentary film to a conceptual haunted house in ADP.

When I was younger, I edited in an attempt to move a piece of writing towards a Platonic ideal of perfection; I thought that somehow, with enough work, a sentence might become pure and untouchable. I have since realized that this is both impossible and completely off the mark. I now edit for clarity in order to enable the perspective of the author to click with that of the reader; to expand the possibility of communion.

So, dear reader, I hope this November issue of The Blue and White resonates with you. If you so desire, we will gladly act as your traveling companion.

Sincerely,

Sona Wink

Editor-in-Chief

Postcard by Isabelle Oh

Bweccomendations

Sona Wink, Editor-in-Chief: Alison Bechdel, The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For. Bill Callahan, “Writing.”

Anouk Jouffret, Managing Editor: John Martyn, “Spencer The Rover.”

Victor Omojola, Deputy Editor: 5 Broken Cameras (2011).

Oonagh Mockler, Illustrations Editor: Amir Levine, Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find -And Keep- Love. Marvin Gaye, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology.)” Milstein, The Barnard Bubble Tea and Sushi Spot.

Annie Poole, Layout Editor: BECKHAM (Netflix).

Siri Storstein, Layout Editor: Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass. Van Morrison, “Days Like This.”

Miska Lewis, Literary Editor: Arcy Drive, “Time Shrinks.” Making breakfast sandwiches. Jhumpa Lahiri, Roman Stories.

Josh Kazali, Senior Editor: Anatomy of a Fall (2023). Brian Eno, “Silver Morning.” Giving up on the struggling succulent in my room.

Becky Miller, Senior Editor: Cruza, Dog Daze. Eva Hoffman, Lost in Translation. Debating the question: “What is the best Beatles song?”

Claire Shang, Senior Editor: Pet Shop Boys, “Too Many People.”

Muni Suleiman, Senior Editor: Hanna Mars, Junie. Chappell Roan, The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess. Japanese Breakfast, "Kokomo, IN." Listening to Brandon Taylor's Love Advice During the Brooklyn Book Festival.

Tara Zia, Senior Editor: Hozier, Unreal Unearth., leg warmers, Wallace Stevens, “The Course of a Particular”.

Anna Patchefsky, Senior Editor: Elvis Costello, “Less Than Zero.” It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia (Hulu). Navy blue.

Sagar Castleman, Staff Writer: Oscar Wilde, “The Soul of Man Under Socialism.” Broadchurch (ITV). Cold apple cider.

Schuyler Daffey, Staff Writer: Gustave Flaubert, Memoirs of a Madman. The Princess Diaries 2: Royal Engagement (2004). The Goo Goo Dolls, “Iris.”

Amogh Dimri, Staff Writer: Rainbow Team, “Bite the Apple,” Fred again.., “Baxter (these are my friends),” Sammy Virji, “Find My Way Home.”

Jake Goidell, Staff Writer: Blaze Foley, Live at the Austin Outhouse

Molly Leahy, Staff Writer: Kirby’s Epic Yarn for Wii. Leftovers for breakfast.

Molly Murch, Staff Writer: Texas, “In Demand.” Tarkan, “Öp.” Cats playing with leaves.

Maya Lerman, Staff Writer: Over the Garden Wall (Hulu). Ruth Ozeki, A Tale for the Time Being. Yellow Submarine (1968).

Michael Onwutalu, Staff Writer: Blue (1993). Sort Of (Max). Gary Indiana, Fire Season. L’Rain, I Killed Your Dog. Sufjan Stevens, “Goodbye Evergreen.” Julian Lucas, “How Samuel R. Delany Reimagined Sci-Fi, Sex, and the City.” “Looking for the Future,” Looking (Max).

George Murphy, Staff Writer: Jantra, Synthesized Sudan: Astro-Nubian Electronic Jaglara Dance Sounds from the Fashaga Underground. Hans von Trotha, Pollak’s Arm. Alexander Lernet-Holenia, Count Luna.

Owen Terry, Staff Writer: John Kennedy Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces. One Sec app.

Vivien Sweet, Staff Writer: Three Colors: Blue (1993). Vince Guardali, The Grace Cathedral Concert. Walking to the Firemen’s Memorial in Riverside Park, and back.

Gracie Moran, Staff Writer: Louise Gluck, The Wild Iris. It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Judith Thurman, “How Emily Wilson Made Homer Modern.” Michael Jackson, “Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough.” The Nanny (Max). Playing the videogame Just Dance on YouTube for free.

Sam Hosmer, Staff Writer: After Hours (1985). J. L. Carr, A Month in the Country. Dada, “Dog.” The dBs.

Jorja Garcia, Staff Illustrator: Dana and Alden, "Dragonfly." James Baldwin, Go Tell It On the Mountain. Good Omens Season 2 (Prime)

Hart Hallos, Staff Illustrator: Watching a ginger woman on Instagram tell me how to communicate with trees through Soul Language.

Phoebe Wagoner, Staff Illustrator: Hey. Stop scrolling. Get a drink of water.

Oliver Rice, Staff Illustrator: Lucinda Childs, Dance. Cocteau Twins, “Athol-brose.” Hannah Arendt. Unironic, dead-serious ceremony.

Selin Ho, Staff Illustrator: The Joy Luck Club (1993). Watching a romance movie when it’s raining outside. The Queen of Dying (Radiolab). Vira Talisa, “Walking Back Home.”

Kendra Mosenson, Staff Illustrator: What’s Up, Doc? (1972). Wallace Shawn, Essays. Making shoebox dioramas. Duck Amuck (1953). Being charming on Ebay.

Jacqueline Subkhanberdina, Staff Illustrator: Hozier, “Moment’s Silence (Common Tongue).” Julie Otsuka, The Swimmers. Walker’s Shortbread Cookies.

Blue Note

Altruism, Butchered

Animal rights activists go to new extremes.

By Vivien Sweet

Amid posters urging students to audition for sketch comedy groups and participate in a sustainable Halloween costume swap, an advertisement for a tasting hosted by Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat stuck out. Something was clearly amiss. Framed by a giant golden retriever looming over a tray of red meat, the event’s description was surprisingly laconic, indicating only “When: Oct, 5, 2023” and “Where: The Sundial.” Beyond a QR code to “visit the farm,” the poster bore few other details.

I’m sure that most passersby instantaneously realized that the poster was a cheap attempt at rousing attention by a veganism awareness organization. But their website took great pains to masquerade as an earnest family farm; I perused nearly half of the site before realizing that the organization was satirical. The giveaway? A listing under the “Vegetarian” section that led with: “Little known fact—pomeranians lay eggs.” (Prospective buyers, a dozen will set you back $1.51.)

Pomeranians don’t lay eggs; this I know. But the lie’s directness caught me off guard. Many parody projects will make claims so explicitly false that everyone can safely laugh at them, eradicating the hierarchy of joke-maker and joke-victim. The punchline of the “Birds Aren’t Real” campaign, for example, is that birds are in fact very real. And satirical organizations that do straddle the line between truth and fiction tend to avoid jokes with troubling moral implications. Yet Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat falls in neither category. Why would an organization fighting against animal cruelty labor to visit colleges, publish weekly articles, and create merchandise to promote a lie? Puzzled, I went to their free sampling in the spirit of investigative journalism.

There was no free dog meat. There was, however, a blow-up husky and eager spokespeople with shirts and hats branded with their choice slogans: “Mmm… PUG BACON” and “Delicious dog, since 1981.” Students remained impassive as they hurried by the stand, having long since tuned out the moral pleas of campus canvassers.

I was the perfect candidate to be wooed into veganism: a lapsed vegetarian, ambivalent about my meat consumption, a lover of both tofu and productive ideological sparring. I spoke at length with a young woman who told me that the advocacy group, founded in 1981 to promote veganism, is family-owned and operated. Although their website explicitly details the process by which the dogs on Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat Farm are (hypothetically) bred, killed, and eaten, they had dropped the act in person. Instead, Elwood’s representatives opted to urge passersby to go vegan for a singular day for the sake of their own dogs.

When I asked why they did not host any fundraisers to directly combat animal farms, she clarified that Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat was primarily a canvassing operation that had successfully converted a nebulous amount of college students to veganism. When I suggested that there were racist underpinnings to the demonization of eating dogs, she argued that all meat consumption should be demonized and helpfully pointed me to their online FAQs regarding accusations of “xenophobia.” (It reads: “Regarding the hurtful stereotypes around cultures that do eat dog meat: we do not condone them.”) We were getting nowhere.

“I’m sorry, I just don’t really see how spreading misinformation is a productive way to promote veganism,” I said.

“What are you doing to fight animal cruelty?” she retorted.

“You have a point,” I admitted.

I left the dog meat sampling perturbed and less inclined to consider veganism than when I had arrived. While walking away, I spoke to some similarly unsettled students—vegans and meat eaters alike—who expressed their frustration at the cruel, ineffective use of dogs in the name of the fight against animal cruelty. “They’re not changing anyone’s minds,” one vegetarian remarked. The merit of their advocacy was irreparably offset by the moral absurdism of their approach.

I was doomscrolling through their website’s FAQ section when I noticed that the rhetoric of Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat had lost all its dwindling earnestness that I gleaned from its canvassers in-person, shifting from an emphatic plea to consider veganism to an altruistic parody of the relationship between animals and humans. “If you were locked in a room with a live dog and an apple, which would you eat first?” the first question asked. In such a situation, I think I would ask to be let out.

“Don’t force your views on me!” another FAQ read. “Isn’t it my personal choice to eat animals?”

The response: “You can choose to be a racist or rapist or beat your children or dog. When you choose to intentionally and unnecessarily hurt others—or eat animals—you’re putting your choice ahead of theirs. Does that seem fair?”

Perhaps not. But what is infinitely more unfair is the flippant whataboutism in equating eating animals to engaging in sexual violence, racism, and child abuse. And the result of such callous, ambivalent rhetoric? Driving away their target audience—meat eaters, who didn’t like being equated to dog killers—and estranging their allies—vegans, who felt that the organization grossly misrepresented their cause.

As the day wound down, the purported dog meat-harvesters deflated their blow-up huskies and rolled up the “free sampling” advertisement that had originally caught my eye. The straggling stream of students had notably begun to swerve around the Sundial to avoid the canvassers, who were still haplessly passing out pamphlets. Without its shock value, Elwood’s Organic Dog Meat was not worth a second glance. Alienating meat eaters and vegans alike, the campaign was a classic case of satire gone horribly awry: a morbid joke taken too far accompanied by a moral imperative forced upon unwilling passersby. In John Keats’ poem “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” a “friend to man” says, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” Perhaps that best explains why I found the falsehoods of Elwood's Organic Dog Meat to be so ugly.

Illustration by Phoebe Wagoner

Blue Note

The Perils of Place

Ed Ruscha’s liminal gas station holds up a mirror to campus.

Michael Onwutalu

Illustration by Hart Hallos

Exactly a month after I arrived in New York, I found myself face-to-face with a gas station. A painting of a gas station, that is: standard, its colors a mélange of light blue and red, but its composition disrupted, made nonstandard, by a magazine. I’d seen it before, yet I was transported, for some 30 seconds, to standing in line in Bush Intercontinental, awaiting the start of the remainder of my life. Rest stops are a manifestation of the liminal: at an interregnum, one succumbs to the pre-destinated suspension of being everywhere and nowhere; which is all to say I was, for that brief and ecstatic half-minute, suspended between everywhere and nowhere.

ED RUSCHA / NOW THEN, at the Museum of Modern Art until Jan. 13, 2024, had been on my radar prior to coming to New York and to Columbia. Ruscha’s early pop shares what critic Nicolas Calas refers to as the movement’s “cool attitude,” except his work possesses a heightened absurdity, a deceptive lightness. His show, encompassing over 200 works and six decades, abounds with the purest of national iconography: four-letter words (a ‘HONK’ here, a ‘SPAM’ there) austerely placed on thick backgrounds; animals that stoke a sense of the surreal; a series of stains.

The gas stations for which Ruscha is best known hew to a distinct vision of American wanderlust: An 18-year-old Ed Ruscha pilgrimaging the Route 66 of Kerouac’s On the Road and The King Cole Trio’s “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66.” Like Ruscha, I was moving, and as such, was made a casual observer of those images: the iconic, austere, surreal, serial. The gas station that so transfixed me was Ruscha’s “Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half” (1964). The artist, ever-epigrammatic, seems to say: The standard is singular, the standard suspends. Consider our meeting a predestined suspension.

I remember arriving to Columbia after months of anticipation to inhabit this place, these blocks spanning 110th and 122nd where everything feels like everything. However, I experienced paralysis when faced with the school’s very placeness during orientation. I moved within the confines of my room and repeatedly asked myself, “Is this it?” as I found everything I needed in white tents a few yards from Furnald. Even with the expanse of 120th and upwards, conferred from the first week of classes in the form of Teacher’s College and the International House, that suffocation du jour still felt inveterate.

That first week gave way to a night-time trip with a friend to the Apple Store that unexpectedly became an escapade. We headed to Central Park for no other reason than just because; I witnessed rats for the first time; we stopped at street benches and listened to the traffic nocturne; we receded to the confines of our overactive minds as we spoke about everything from James Baldwin and Theodore Dreiser to Kelela; we made our way back to campus after getting lost in Central Harlem. Dwelling within New York was exhilarating. Any remembrance of my relation to Columbia faded away as the smell of trash entered my nose, my eyes scanned the aged brownstones, and the patois floated around my ears—a diasporic mating call.

Contrary to popular belief, there’s an artifice removed when in movement—when scaling an area, a place, a condition. Ruscha’s exhibition, an eclectic, dizzying motley, required uncomfortable sobering. Plastered words grew terser the more of them you saw; the places were remote, isolated, quintessential; and Ruscha, forever self-referential. I proceeded through rooms and decades, bore witness to states of torpor and disorder. I began projecting motifs from my own campus life onto the works: equivalences, motifs my mind could latch onto. My “Standard Station” was JJ’s; my “Jumbo” (1986)—a hazy, grayed elephant climbing upwards—was me climbing eight floors of Schermerhorn stairs; and “The End” (1991), exactly what it says, was nowhere in sight.

“Oh boy, my first visit to New York was a total shock,” Ruscha notes in a 1980 interview. “I was thrown back by the coldness of it. I didn’t know anybody there. I remember I was just overwhelmed because of the number of people there and the impersonality of the whole place.” Replace New York with Columbia and you have something so familiar to me it’s unsettling. Though in New York, Columbia is not New York; it’s taken me some time to realize that. I’m more myself and at home when off-campus, where I’m untethered—a nomad, however démodé. Coming, staying, leaving. I’ve been making strides to define a place at Columbia, but my incredulity refuses. The more I travel outwards—north and west, south and east—my arrival predicates a leaving: This was never it.

Blue Note

Long-Term Parking

A tribute to a forgotten pocket of campus.

By Sam Hosmer

Last semester I encountered a sealed, abandoned, turn-of-the-century Otis elevator hiding at the bottom of a disused shaft in the East Asian Library stacks.

Picture the following scene: a vaguely aquamarine, very sooty chain link cage with a single-bulb light fixture fastened to the ceiling; a brass scissor door, jammed open at right; and an inspection certificate on the far wall, good through 1980. On the right there is a panel of buttons set into a hefty brass faceplate; to the left, there is a yellowed, typewritten library directory. Graffiti above it reads, “Impeach Nixon.”

It is my curse as an explorer of campus’ hidden and obscure mundanities to perpetually discover that most of the hatches and doors I open reveal nothing but boring service panels and utility equipment. Yet, here was a perfectly preserved historical artifact, embalmed in dust and hiding in plain sight, replete with surviving ephemera and the ghosts of patrons past. Standing in front of the thing, with my neck wrenched through the hatch, I could almost hear the clamorous, resonant grinding of old elevator machinery.

The sages of campus history, intimately familiar with its preeminent architectural narratives, were stumped by my discovery. It became clear that, as a piece of utilitarian machinery, the elevator never had a place in that world: it was too quotidian, too mundane. Rather, the elevator and its intact artifacts are archaeological evidence of a different world, a banal one, a world populated by the rote, perfunctory, trivial routines of daily use. If I wanted to know more, I would have to dig for it.

I trawled the archives and chased dead leads until I found out that Marsha Wagner, recently retired from the Ombuds Office, worked in the library around the time the elevator was decommissioned. I emailed her. Within 30 minutes, I received an enthusiastic reply copying several former colleagues; 24 hours and two connections later, I was talking to Ken Harlin, who used to park his bike in the old elevator’s machine room.

As an architecture student, I am preoccupied with the ways that buildings age. To borrow a tired cliché, Columbia’s campus is best viewed as an evolving textile, in which the constraints of urban density and a perennial shortage of space require constant adaptation, reconfiguration, and replacement. The tantalizing products of that ongoing, overlapping process of fission and recombination are these mundane spaces, once used by so many without thought and now utterly, unceremoniously forgotten. They are still sitting among us, in the walls and under our feet, waiting for us to find them.

On its own, an elevator might have no historical resonance. But that is a false assumption made on the basis of its exclusion from campus’ more spellbinding architectural narratives, one enabled by our position as uninitiated onlookers, inhabitants of contemporary reality, with no direct connection to it beyond its unexpectedness and our curiosity. So, picture the ordinary spaces you use every day: the pathways you walk on to get to class, the doors you open when you enter a room, the room itself. These are the scenery for our experiences; they are, despite not having their own independent meaning, intractable from our lives, and therefore deeply personal. It’s no surprise, then, that if you ask the right person—if you find your Ken Harlin—their enthusiasm will betray that these bygone spaces aren’t actually mundane at all.

Try to remember your own mundane spaces. You never know when they might end up as someone else’s discovery. And, once Kent reopens with enhanced fire suppression and a new lease on life, go check out our elevator—but don’t tell anyone I told you.

Harlin, who for many decades has been the library’s Access Services Manager, told me that our mystery conveyance was still in use when he joined the staff in 1969. In 1980, when the library was renovated, the elevator was replaced; costs to remove it were prohibitive, so the shaft was sealed and used to run cabling.

To the best of his knowledge, there are no immediate plans to remove it. Thus, in the basement it will stay—along with his bike, which, as far as he knows, is still there.

Our elevator is a perfect example of the poetry of a quiet, forgotten place. When history’s main attractions are abstracted over time and delivered in the pages of a book or a lecture, intrigue comes from the imagination, which brings its own distinct joys. But the banal and ephemeral—the unremembered elevator, the fervid political graffiti etched on its walls—deliver history in the form of palpable, tactile, dust-embalmed reality.

Illustration by Emma Finkelstein

Blue Note

Chicken Hunt

Our costumed writer tackles the neighborhood bar scene.

Amogh Dimri

Amid September’s first-month fervor, my friends and I decided to reinvent the wheel when it comes to the age-old college quest to get drunk. The premise of our Saturday night escapade was simple: a group of, say, 15 people each pay one person $15. This lucky individual dons a full-body, bright yellow, faux-feathered chicken costume and hides at a bar near campus, ordering as many drinks as they like with the pooled money. In groups of four, participants hunt for the “chicken” who could be at any given bar on a list of eight or so. If a team visits a chickenless bar, all members must finish a drink before leaving for the next destination. The winning group not only receives bragging rights and free drinks until the collective money pot is drained, but also the opportunity to become the chicken during round two.

It was my idea, so it was only right that I volunteered to be the inaugural chicken. While the game came to me algorithmically via TikTok, it was confirmed as an authentic British tradition by my roommate, who had just returned from studying abroad at Oxford. The bars we’d selected made for an almost comprehensive list of Columbia hall-of-famers: Mel’s, The Heights, Amity Hall, Lion’s Head, Arts and Crafts, Dive 106, and Nobody Told Me. Honorable mentions included The Craftsman, The Hamilton, and The Expat, which we agreed may not appreciate a loitering chicken and drunk hunters interfering with their ambiance.

My hunters gathered on a Saturday night, with a mere two of the 16 following the last-minute suggestion to dress as farmers. After allowing some gawking at my glorious felt comb and wattle, I made use of my 15-minute head start and departed for my chosen destination: Lion’s Head. To me, the choice was clear. Not only would the bartenders not bat an eye at a grown chicken-man, but it was far enough from the starting line at East Campus to keep the game interesting.

Being a chicken on the run is lonely work. Fortuitously, I ran into a high school friend on my way to Lion’s Head and swept him under my wing. With money to spare and a newly co-opted drinking buddy, we strutted up to the bartender and asked, “Your most expensive drink on the menu—we’ll take two.”

To our immense disappointment, it was a $13 espresso martini. In my noble effort to keep the game lively for its hunters, I chose an affordable location and squandered a golden opportunity to ball out with my friends’ money. Only at this point did the unamused bartender look me up and down. “I’m gonna need to see some ID.”

. . .

We sat in the back, far from any windows, sipping on our espresso martinis (and a few consolation IPAs each). Next to us, a posse of five older army veterans could not get over the chicken costume. It took just 10 minutes before the first group arrived, followed by the second a few minutes later. Lion’s Head came alive amid jeers and a frantic hustle to the bar to order on “the tab of that chicken over there.”

My friends in the winning group—my favorites—insisted they had an instinct that Lion’s Head was the optimal spot: Beer, cheap drinks, and a bar culture accepting of a roaming chicken made my coordinates obvious.

The runners-up had also thought strategically: Lion’s Head’s shots were $5. If they had guessed wrong, they could pound some tequila and keep it moving. They also told me they were confident because “What other animal lays eggs besides a chicken? That’s right, a lion.” Perhaps they pregamed a little too hard. Group three crossed the street from Amity Hall; while perhaps too nice for a chicken, the size of the bar, they insisted, would have led me to pick it for our large group. A couple more beers made their way round the table and the pooled money was drained.

The bankrupt final group arrived about 40 minutes later after going to The Heights, Dive 106, Mel’s, and Nobody Told Me. Evidently, their decision to route down Broadway before cutting over to Amsterdam brought their downfall. When they asked The Heights’ bouncer if he had seen a chicken, he remarked: “A chicken? If I saw a chicken walk in here, I would have had to take my phone out and take a photo!”

With the group reunited, we decided to make a pilgrimage to The Heights to end the night, the reliable fall back for frozen margaritas and an open rooftop. As we entered, the bouncer informed the Group four folks behind me, “The chicken is here now!”

What people don’t tell you about chicken costumes is that they are, if you will, a chick magnet. After chatting with The Heights’ bartender, we learned it was her last night working. To honor the auspiciousness of a chicken visiting on her final night, she connected her phone to the bar’s speakers to blast the Chicken Dance song for all of Broadway to hear. I embraced the ethos of my character one last time and danced in all my felt-feathered glory on The Heights’ roof for the captive student onlookers.

Illustration by Betel Tadesse

Campus Character

Chambit Miller

By Sofia Pirri

On Aug. 26, 2023, Chambit Miller, CC ’24, was at a fried chicken restaurant in Lima. Surrounded by her Peruvian lover and his friends, she suddenly remembered a dream in which she died and felt herself being pulled into a vague light source. Boarding her flight home that night, Chambit convinced herself the premonition was real: the plane would surely crash. Under the influence of this dark conviction and her recent reading of Camus, she began to write. Thankfully, Chambit survived. Her journal of philosophical musings remains intact.

I met Chambit several days before the start of freshman year, when we moved in together. In our dingy apartment, the neon pinks and purples of her incense-scented room created an oasis. My other roommate and I would gather like children on her bed, listening to her talk about film or regale us with absurd tales of her high school shenanigans. She can seamlessly weave her innate sense of humor with profundity. “If you don’t have humor, how can you survive in this world?” she asks. “You know, Sisyphus should have made a few jokes.”

Illustration by Oliver Rice

Others may know Chambit through her role as president of Columbia’s literary fraternity, Alpha Delta Phi. You might have seen her rolling a cigarette on Low in Tabis and an orange leather jacket, sharing the fruits of her labor with a small entourage. Or perhaps you’ve run into her in line at a club, where you waited for hours and she waltzed in with a few words to the bouncer.

To some, her presence is beguilingly enigmatic. But Chambit rejects the label. “I feel like I’m an open book,” she explains. Minutes later, she opens her journal and unabashedly reads me her Lima doomsday entry. “I’ve really lived my life. The only thing I would be regretful about is not having experienced love and an orgasm.” She takes a beat. “You can put that in there.” Chambit’s frankness doesn’t detract from the enigma, it enhances it. How could someone so honest retain such a marked air of inscrutability?

For starters, Chambit seems to be on the cutting edge of everything: indie film, hyper pop, edgelord memes, and the Brooklyn rave scene. Her extreme cultural awareness belies her own work as well. A recent painting called Hunter Biden Smoking Crack in a Sensory Deprivation Tank is a perfect example of the way in which Chambit doesn’t just have her finger on the pulse of the generation; she moves a beat faster.

In addition to visual art, Chambit is also a filmmaker. She is producing a documentary tracking the effects of gentrification on three Lower East Side families. Chambit’s refusal to constrain herself to a single medium brings both anxiety and opportunity. Though she fears becoming a master of none, she finds comfort in a piece of advice from a friend: You live your life as your artistic medium. “I want to live a more project-oriented lifestyle,” Chambit tells me. Such projects include running a bed-and-breakfast and founding “the Miller Institute of Excellence—a private, for-profit education.” This seeming irony is underscored by an acute awareness of economic possibility. “You can do so much with money,” she explains.

Therein lies the crux of the enigma. Though she has a strong desire for authenticity and creative autonomy, Chambit’s quest for tangible success compels her to commercialize herself. And she is surprisingly good at it. The first result of a Google search for “Chambit Miller” is her own professional website. Her LinkedIn has 500+ connections and details an impressive array of internship and student group experience. Her bio: “I do many things” (no punctuation). In short, Chambit has learned to commodify her vibe. I noticed a barely perceptible shift in her demeanor the moment I began recording. Upon a standard request for pronouns, Chambit turns her uncertainty into a bit: “She/her. Uh, she/him! Wait.” She lets out a raucous giggle. “On the low, I’m she/him because most times I am she/her but sometimes I am him.” When I ask if she considers herself an artist, she takes a long drag of her hand-rolled cigarette while pondering her response. Though this persona often borders on pastiche, it is indicative of her ingenious ability to mix the earnest with the delightfully satirical.

I wonder if Chambit would defend her own ability to self-commodify. She is saddened by her younger brother’s dream of an easy-money job and disappointed by Columbia students’ lack of revolutionary thinking. “I thought people were going to want to change the world here.” Instead, Columbia taught her about consulting. While Chambit may disparage the more corporate strain of materialistic pessimism, she remains motivated by the fast-approaching doom of post-grad life. Chambit has found a way to navigate this paradox with a recent passion project: her collective production group Xenia, named after the Greek principle of hospitality.

Recent events include a music video shoot with hyper-pop duo MGNA Crrrta and concerts with Xaviersobased, Clara Joy, and Frankie Cosmos. The last few times I’ve spoken with her, Chambit has been consumed with writing workshops, auditions, and rehearsals for Xenia’s Columbia debut: a three-act haunted house play based on research from ADP’s archives. Through the collective, Chambit has built a project to which she can devote herself professionally while also establishing her dream of a diverse, boundary-pushing creative community.

Of course, no account of Chambit would be complete without examining her role in the literary fraternity itself. When I walked over to the 114th brownstone for a jazz night, I found her playing security guard on the stoop in a plaid robe, hoodie, and crocs, ushering a stream of students out onto the street. She told me the event was ending because several members were downtown supporting someone in legal trouble. Before I knew what was happening, she had already called an Uber to the courthouse. Why bother going so late at night, I asked. Surely no official court proceedings could take place at such an hour. She shrugged. “All of my kids are there.” The family she has forged within the society is perhaps the strongest testimony of Chambit’s capacity to create something tangible and lasting.

Despite her propensity for leadership, Chambit constantly swaps her trademark brash confidence for self-doubt. After every inflammatory one-liner, she adds, “Wait, don’t say that,” or “Is that cancellable?”, and, ultimately, “You can write about this, fuck it.” Chambit agonizes over her legacy. Her morbid journal entry from Lima this summer makes sense given this underlying existential anxiety. When I ask Chambit what scares her the most in life, she bluntly confirms my suspicions: “dying with regrets.”

During the historic 2022 European heat wave, Chambit walked the Camino de Santiago with zero physical preparation. She went to figure out the purpose of her life. Let’s hear it, I say, and she gives me a working definition. The temptation to share it here is strong, but I remember how quickly she changes her mind. No, I cannot put her ostensible life’s purpose in print. Chambit once told me, “I feel like I might be on the brink of something great, but also on the brink of something awful.” I suppose only time will tell.

Campus Character

Samara Huckvale

By Muni Suleiman

The opening sequence of Them (2023) features main character Ira’s vibrant pink boots, jacket, hair, and hat, contrasting with an otherwise bleak winter afternoon in New York. I am greeted by equally vibrant colors upon entering the dorm of screenwriter, director, and joined-Letterboxd-when-it-was-still-in-beta senior Samara Huckvale, CC ’24.

Them, Huckvale’s directorial debut, recently won the Marvels of Media Festival’s Award for Best Student Narrative Short. The festival, hosted by the Museum of the Moving Image, champions autistic media makers of all ages and skill sets. When I asked how neurodivergence factors into their work, Huckvale immediately jumped to recall a Letterboxd review of Them from an internet friend: “You can tell a neurodivergent person wrote this!”

Illustration by Justin Chen

At the heart of Them rests an awkward social dance that Huckvale witnessed between two friends. Contrary to most, Huckvale revels in the tension that arises when navigating conversational norms. Their affinity for the awkwardness underlying the Black experience, in particular, is evident in their love of Issa Rae’s Insecure. “Everybody wants to be Issa, but they’re not Issa,” they told me. “I feel like I’m a Kelly. She eats.”

Them imagines a reality in which people take more chances creating friendships with the people around them, even if social interactions are harder to navigate as a neurodivergent person. “The character to me is autistic, some people can read it as social anxiety, or it could be both,” Huckvale said. “I just feel like there’s not a lot of stories about friendship, how important that is, fostering one, and putting yourself out there [to] create some really meaningful relationships.”

Deep friendship not only drives the plot of Them but forms the very ground upon which it stands. Indeed, Huckvale admits that it takes a village to make a film. They called upon their internet friends to inform many aspects of the film, from the set design to the soundtrack. While working on the film, Huckvale prioritized and dedicated it to the specific marginalized community to which they belong: “I wanted to keep the whole cast, crew, everybody that touches the film to be Black and queer. I don’t think anybody else would get the message.”

In their childhood, Huckvale always managed to find themselves in front of a screen, whether it was bonding with their father through frequent trips to the movies or simply watching TV. Their love went beyond idle consumption. “I used to memorize scenes. This is literally just autism,” they joked. “I remember full episodes and I played them through my head and acted them out when I was alone.”

Huckvale’s resounding commitment to cinema is all the more surprising in light of the fact that they were admitted to Columbia as a chemistry major. Published in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry as the first author on a study finding a positive association between GlycA, an inflammatory biomarker, and depression, Huckvale once wanted to be a chemistry professor. In retrospect, they said that becoming a chemist felt much less like a desire and much more like an obligation.

Huckvale also felt a lack of belonging and creativity in STEM compared to the diverse community they’ve found through film. The value that Huckvale holds for friendships heavily ties into their feelings about the Black queer experience, especially since they grew up in a small white town in Texas. Deep care for their community and mutual responsibility drive their work, which acts as a way to pay it forward. “I don’t think I would be alive right now if it wasn’t for my friends who are Black and queer … In this world, when we’re all one or two steps away from being on the street, it doesn’t make sense for us not to be together,” Huckvale expressed.

Huckvale also cares very deeply about how their work is perceived by other neurodivergent people, as they strive to represent that worldview while acknowledging that neurodivergence looks different for different people—a nuance not often explored by existing film depictions of neurodivergence. Huckvale elaborated, “Every canon autistic character I know of is a joke or a caricature of themselves. I have some characters [in mind] that I think are autistic, but I don’t think the filmmakers know that they wrote autistic characters.”

…

As a Black filmmaker, Huckvale is heavily inspired by the works of major Black directors. Watching Jordan Peele win the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay in 2018 for Get Out (2017) and Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) made Huckvale believe that they could become a serious filmmaker.

There are, of course, also challenges to being a Black creative on campus. Throughout our digital correspondence over the past three years, we’ve connected over the frustrations of having to over-explain the relevance of subject matter pertaining to race in our respective creative writing classes. After remarking on the lack of Black queer people within Columbia’s film program, Huckvale recounted an experience in a screenwriting lab much earlier in their Columbia career. Huckvale was presenting 16. F. Dallas., a short screenplay about a queer youth trying to understand their sexuality online, when someone asked them quite bluntly, “What’s the point of even writing this?” 16. F. Dallas. went on to win a Short Screenplay Writing Award at the 2022 Urbanite Arts & Film Festival.

Huckvale’s most recent writing project is their senior thesis film, a high school comedy with similar sensibilities to Olivia Wilde’s Booksmart (2019) and Emma Seligman’s Bottoms (2023). They hope to act as a main character in it as well. Columbia’s thesis films are traditionally a five-minute affair according to Huckvale, but their thesis film would act as a proof for a much longer feature film.

Since it will be completed for a Columbia class, Huckvale has formal restrictions that all participants must be Columbia affiliates. However, Huckvale meets this challenge head-on. “I think it's pretty cool that everybody [working on the film] is in our graduating class. I think it’ll be a nice little time capsule for people,” Huckvale smiled.

As for after graduation, their immediate priority will be working on a documentary on the experiences of Black, trans, and autistic people. They feel that a major factor in the high levels of undiagnosed autism within the Black community is the poor representation of neourodivergence in popular media. “People don’t know what autism is,” Huckvale explained. “I want to talk about what that means, being an undiagnosed person with all these other marginalized identities.”

I noticed a unique sense of urgency from Huckvale as they relayed their post-grad plans to me: make the documentary, attend grad school, and eventually crack the industry. This urgency is driven by their belief that “there’s a lot of stories for me to tell here and help other people tell.”

They have a similar urgency to get off the app formerly known as Twitter, where we built a friendship in our digital freshman year and where they might be considered a micro-influencer. “I should have shut up a long time ago, but it’s great that people can see my work that way,” Huckvale rationalized. “That’s why I feel like I need to make more stuff before the app burns.”

In addition to carving out space for Black queer and neurodivergent creatives within the film world, Huckvale is also currently plotting their future collaborations with Ayo Edebiri and Jordan Peele. Before concluding our interview, they requested that I do my part to honor this manifestation by putting it in writing. However, I get the feeling that Huckvale doesn’t need much manifestation to get where they want to go.

Essay

Ousmane and I

What the father of African cinema taught me about independence and being alone.

By Victor Omojola

“Back in Dakar they must be saying: ‘Diouana is happy in France … She has a good life.’ For me, France is the kitchen, the living room, the bathroom and my bedroom. Where are the people who live in this country?” Black Girl (1966)

…

Shot in as illuminating a black and white as I have ever seen, Ousmane Sembène’s La Noire de… (Black Girl) follows a young Senegalese woman named Diouana who travels to Paris to work for a wealthy family. Confronted with the contradictions of European colonization through her racist employers, who at times feel more like captors, she quickly begins to question whether the wage she is paid and the “modernity” she is offered by France are worth her plight.

I was around 11 when my dad dragged me to the academic conference where I first watched Black Girl. I remember feeling like a children’s toy, taken from a box set and thrust into an awkward setting where I did not belong. This is all to say that that day, I think I felt a little bit like Diouana does in Black Girl. Surrounded by people I didn’t comprehend, a child among a sea of academics, I felt particularly alone. It wasn’t the first time I had felt this way, and I remember realizing, while watching Diouana, that it certainly wouldn’t be the last. Black Girl is largely about the consequences of the alienation inherent in systems that have governed the world for the past few hundred years. At the end of the film, Diouana decides to kill herself.

These days, it seems for many that finding a community where you belong, not to mention harnessing its collective support, is a nearly impossible feat. Surrounded by tens of thousands of students who are themselves surrounded by New York’s millions, I, too, often catch myself asking where all the people are.

Essayists and experts have attempted to solve the riddle of loneliness in the country’s most widely-read publications. According to them, the solutions are perhaps elusive, but nonetheless straightforward. In a New York Times essay titled “We Know the Cure for Loneliness. So Why Do We Suffer?” Nicholas Kristof argues the U.S. should install a Minister of Loneliness and encourage people to eat more meals together. Other pieces from The Conversation and Forbes focus on the effect of the problem in the workplace, suggesting that CEOs can increase corporate value by combating loneliness. Many cling to the idea that the problem is a particularly male one, proposing pickleball as a potential remedy. The U.S. surgeon general refers to the dilemma as an epidemic. Even Hillary Clinton has chimed in.

I’m not as certain as the former Secretary of State that I have all the answers, but I’m also not sure the answers are as attainable as many of these pieces posit. I think part of that is due to a mischaracterization of being alone as unequivocally negative.

…

I can’t remember the first time I saw a movie in theaters by myself—it’s been my preferred means of seeing them for a while now. I’m assuming, though, that it was sometime shortly after the height of the pandemic. I’ve never had an abundance of friends, but in that Covid-heightened limbo between high school and college, I found myself with a particular lack. I turned to the screen to alleviate this paucity. My theater of choice quickly became Amherst Cinema, an arthouse theater in the heart of the Pioneer Valley. Its independent nature became a crucial feature of my experience as a movie-goer, even after I moved away from Western Massachusetts.

The independent theater cannot substitute a close pal, but it has served me well as a wise, old tutor. Whether it’s a brilliantly comedic crash course in post-Civil War Black migration (Buck and the Preacher (1972)) or a comprehensive overlook at the father of video art (Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV (2023)), I know that each time I leave the theater, I will walk out understanding something new about the world and myself.

In this way, the movies have been my other university. The sum of hundreds of matinee discounts: my secondary tuition fee. Sembène and filmmakers of his ilk: my impossibly sagacious instructors.

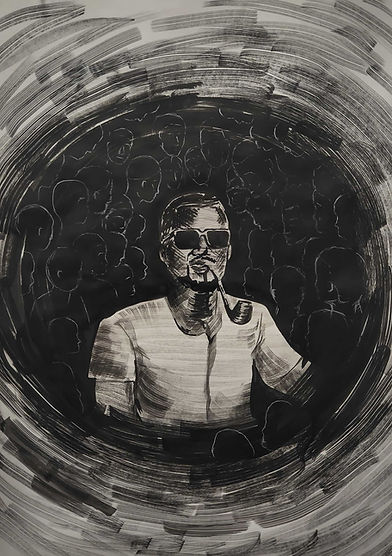

Ousmane Sembène was born and raised in Ziguinchor, Senegal, before he was drafted into the French army during World War II. His 1975 film Xala—equal parts sex comedy and political satire—is about the way in which France’s lingering influence on a purportedly independent Senegal has hampered the progress of its people. In my favorite photo of the filmmaker, he is surrounded by people. His signature pipe balances between his lips and his black sunglasses perch on his nose, unable to hide his cool gaze from staring directly into the lens. To me, the photo is not only a reminder of Sembène’s authorial magnetism, but also of the way he centered his community in the stories he told.

Illustration by Jorja Garcia

Filmmakers of color like Lino Brocka, Sara Gómez, William Greaves, and Sembène spent their careers using the moving image to redefine their position as colonial subjects. However, Western distribution monopolies made it nearly impossible for people to see their work, not to mention the censorship from their own governments that hindered their most ambitious visions. In response, these directors worked outside of established norms of production in order to complete their projects.

We might refer to this mode of operation as independent filmmaking. And yet, such works tend to be excluded from popular discourses about indie film.

Certainly in a filmic context, the “indie” category does not solely refer to how a movie is produced. Films deemed independent are still often made with large budgets, and many are produced within a Hollywood studio system. Cinematic technique, thematic content, and the subjects that are portrayed, are, at the very least, just as relevant when considering whether a film is considered indie in popular discourse. In Indie: An American Film Culture, Michael Z. Newman explains that many indie films are quotidian in scope, offering representations of “ordinary people and their indiscretions, foibles, and minor key victories.” Indie films in “the popular imagination” tend to have meandering narratives where characters don’t do much more than talk to one another. Think Ben Stiller’s Reality Bites (1994) or, for a more modern exemplar, Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha (2014). Substantively, the general indie film aesthetic consists of long takes, realistic dialogue, and a focus on “everyday people.”

The issue here, however, for Black and other non-white filmmakers is that these visual cues are heavily associated with white American and European cinema. Indeed, films from the “Third World” are often categorized under the radical criterion of Third Cinema, a film movement started in the 1960s by Latin American directors and theorists, even if they are much better suited for the “independent” tag. As articulated towards the end of Medicine for Melancholy, Barry Jenkins’s debut feature, “everything, everything about being indie is all tied to not being black.”

It doesn’t help that academic institutions reinforce Jenkins’s point. At Columbia, I have often heard professors express a desire to expose students to underseen, unconventional works. Yet I have been astounded by the number of courses offered that entirely neglect African or Latin American films. I have sat in classes that were meant to cover decade-long periods of “cinema history” that failed to feature a single film by a non-white director from the Global South.

The exclusion of the Black film from common conceptions of the independent film is not dissimilar to the contemporary discourse concerning loneliness. Like Diouana was forced to confront firsthand, in a world haunted by colonialism and racial capitalism, the Black subject is almost always systematically isolated.

…

As I’ve read essay after essay over the past few months, seeking remedies for solitude, one piece has stood out. The Malignant Melancholy by Amba Azaad splits the contemporary loneliness crisis along a binary. “There are, broadly, two kinds of structural loneliness. One is the benign loneliness of the socially alienated, the other the malignant melancholy of the erstwhile master,” she writes.

Like Azaad, I see something absurd in who exactly is centered in the current conversation surrounding loneliness. She argues that men (I would emphasize, white men) decry the unkind and isolationist norms that cause their social suffering, but fail to see “any rigorous structural analyses of their culpability in oppression.” I’ve read far too many essays in which those who benefit from the societal norms which render them lonely center themselves in this discussion. Everyone suffers from the day-to-day loneliness that is manifest in a society that depends on alienation. But poor people, racial minorities, the LGBTQ community, and immigrants are, like Sembène’s Diouana, additionally oppressed by virtue of who they are relative to their surroundings. A secondary, more weighty loneliness is wrought by this reality.

As a Black man who moved to the United States at a young age, I recognize this dichotomy in my own life. In a broad sense, I have come to realize that I experience loneliness not just because I live in a society that thrives on individualism, but also because I’ve spent my life dealing with institutions that are riddled with anti-Blackness. The latter of these, however, becomes so regular that it becomes mundane.

Just as the indie film world tends to present an image of whiteness as the heuristic through which the independent film is recalled, ultimately neglecting the stories of racialized people, the narrative around modern loneliness, too, largely excludes the Other, the oppressed.

…

It did not take long for my love for independent theater to develop into a desperate desire to work in the world of independent film myself. I voraciously began to write scripts, work on student sets, and seek out internships, all in an effort to ensure that one day it would be my own work showing to a two o’clock crowd of a dozen or so retirees on an insignificant Tuesday afternoon. I saw the independent film world as a haven of unbridled creativity and ambitious storytelling—a staunch challenger to the world of Hollywood profit-prioritizing and adaptation-mania. I still think I do.

However, as I spent time on (predominantly white) independent film sets, I started to see all that they left to be desired. The working environments of many indie films were just as under-paid, long-houred, and occasionally-abusive as those in industry projects, and these flaws were merely hidden by an aesthetic of nonconformity. I still admire much of the work being produced by young, ambitious voices, but I was forced to acknowledge that these works are not always created in arenas of harmonious horizontality. I have since wondered just how attainable that image of Sembène, surrounded by a cadre of collaborators, actually is.

The independent film world’s more structural problem lies in the fact that it, too, has become an industry. For those the godsons of producers or nieces of executives, making it to the indie-sphere is a simple road. For those of us who are not, a more precarious pipeline is optioned: pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to attend a top film school, make contacts within the world’s top independent film festivals and distribution companies, submit to those festivals re: those contacts, and sell rights to those distributors re: those other contacts. In short, the American independent film is not as liberated as we might think it to be. A wealth of connections is the barrier to entry to the world of independence and a wealthier background goes a long way in surmounting it.

To make matters worse, current distribution patterns seriously limit the audience for these films. There are few truly independent or arthouse theaters remaining, and the insular crowd they tend to draw is predominantly white, wealthy, and old.

It’s through the imagination of film researchers and artists of color like Sophia Haid and Keisha N. Knight, who recently curated a series on the U.S.-Mexico border for asylum seekers, that we can reenvision film distribution. They yearn for a future where Sundance is no longer “the beginning and end of all things independent film in the United States”: a future in which movies are shown to people who might be impacted by them, because they respond to discourse that matters to them.

This would mean valuing innovation over intellectual property intended for adaptation, crafting challenging narratives over hollow ones, and ultimately, placing process over profit. If these sound more like hurdles associated with Hollywood than the independent film space, they are. The idea of the independent film only emerged in opposition to the rigidity of the industry. A true solution to its issues would require also solving Hollywood’s. Unfortunately, the ugly greed and brazen disregard for working class people recently displayed by studio heads makes one feel the prospects of that happening anytime soon are highly unlikely.

…

As Azaad contends, loneliness is largely a byproduct of the hierarchies that organize modern society—racism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, capitalism. Though these systems ultimately harm even those who have the most to gain from them, these privileged individuals still generally favor their continuation. They want to have it both ways: They wish for their loneliness to subside so they offer solutions that amount to “being kinder to one another,” but they reject any critical evaluation of the conditions that produce their loneliness in the first place.

Like independent film’s incestuous industrialization, our universal plague of loneliness is wrought with contradiction. For young people like myself, who in their marginalization recognize this irony, I would encourage a reconceptualization of loneliness. Indeed, I am coming to realize that though my identity at an institution like Columbia can be extremely isolating, it has also led me to examine how I might best contribute something worthwhile, even when institutional forces stifle my vision. It has compelled me to reconsider my values as they pertain to the film world and the “real” world. If there is one thing that I have learned during my time at this university, it is that resisting hegemony is my priority. It is a simple lesson, but it is an actionable one: all it takes is asserting the value of my own narrative. I owe a lot of this to Sembène. He has taught me the importance of telling stories about myself and my community.

As far as loneliness on campus goes, resistance looks like leaning into my position as a socially alienated subject and forming incredibly close bonds with the relatively few Black students at this school. I think that a prerequisite for finding community is finding out who you are, yourself. Ideally, this is the transformation that births the independent filmmaker: from someone who wanders in the wilderness, alone in their distinct perspective, into someone who, in recognizing their positionality, allies with those who share their marginal status in order to challenge the industry and substantively change it. From one sort of independence to another. From loneliness to liberation.

Centerfold by Hart Hallos

Measure 4 Measure

Selected Poems

By Sofia Whetstone

Wood Mirror

Dip down your wings in the dune

slippery log

jump frog

step on a snake

wade,

hands hover over lake

(that young sprite did sure make me quake)

ta-ta ta-ta ta-ta -ta

I think of the in our climbing tree

Endless s

a

p

A spring blossom with sap… even in winter!

God were we blessed!

And they cut down the tree

and we moved a decade later

and Dad thought he was a savior

so sometimes I wonder:

Are we cursed?

Didn’t even pick at the sap, (stuck my finger in it sometimes), didn’t take leaves and there were no apples to give. Cutting it down was original sin? I wasn’t raised religious. Not being raised religious was original sin? Not being religious now is original sin?

I don’t buy it.

I look at my own

Music Box

How much between [now] and [becoming the mother of your children] I know not.

Maybe the universe will explode once or a few times,

maybe it won’t explode, not at all. I know you hope for this.

[this]

This being twenty two. What is?

What gives?

That tree for one. The lady one on 122nd between Amsterdam and Broadway. The one Rahna ate from.

Prince says “I feel for you.”

He moans and mumbles some and with that guitar he sure does strum: “I think I love you,” mhmm

[mhmm, baby]

Mhmm like a swirl in a box. Touch your finger against the corrugated rim. That squiggly In-Between.

Mhmm breaking down boxes at dusk, mhmm corrugation like honey

Those steps taken late and cold in the winter,

and the moon on the snow

Mmhm,

I center myself in it.

(I let it linger)

Mhmm honey, mmhm

At Two Swords' Length

Did You Pass the Background Check?

By Amogh Dimri and Molly Leahy

Congratulations on being admitted to INSIDE THE SITUATION ROOM with Former United States Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton. To complete your background check, please write your name, Social Security number, and address in the attached spreadsheet. Then follow the directions below to encrypt the form and email it to:

usss.dhs.gov.baldeagle.patriotism.f-16fighterjet.mcdonalds.obama.guns@gmail.com.

Affirmative:

I passed the background check with flying colors.

Name? I’m Him. Social Security number? 1. Address? 10 Downing Street (Well, the attic when it’s not booked on AirBnb). I am the Columbia University Political Science major: 5.0 GPA. Wrote the Dean’s List. Weekly tea time at the President’s Mansion. SIPA’s dean practically begged me to enroll in Hill’s course. (She must’ve noticed my #I’mWithHer tramp stamp.)

And now here I am, sitting in IAB 417, humbled by the aesthetic and symbolic glory of Hill’s iconic pantsuit (C’mon, Feminism). At this moment, I am nothing more than a boy, sitting in front of a girl, asking her to love him. And she will. I’ll make sure of it.

At 3:40 p.m., we get twenty minutes for a Q&A. That’s twenty minutes to change my life—and Hill’s—forever.

I stand up and take the mic. “Trevor, Madam Secretary. Trevor Smith—like Adam, only living and handsome. Senior at Columbia College studying Political Science with a concentration in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. I’ve been passionate about politics since the first grade, which is when I organized my first political campaign—‘Trevor for Class Monitor: He Gets the Job Done.’ I ran on a platform of sand in the sandboxes and text in the textbooks. After my first year at Columbia, I took time off to establish my own for-profit—A Politician Without Borders—and visit countries like Sweden that clearly need their political priorities straightened out. My professional goals include: becoming the first person to serve simultaneously as President of the United States and British Prime Minister. My question for you, Madam Secretary, is: Can I have a job in the White House? Thank you.” I sit back down.

Hill pauses, clearly bewitched by my mojo. “Okay, Trevor. You can have a job.” She snaps her fingers, and, all of a sudden, we disappear—just me and Hill—from IAB 417.

As my surroundings start to come into focus … I see … so much mahogany. And … are those desk pads? I look up: Hill, stands at the end of a disconcertingly oblong room, in a kickass pantsuit, pointing to a huge map.

It hits me. We’re in the Situation Room. I knew she was powerful, but I had no idea she was this powerful. “Trevor!” she bellows to me from across the room. “You said you wanted a job, right?” I straighten up in my chair. “Yes, Madam Secretary.”

“Great, because we’ve got a job to do right now.”

I look to where Hillary is pointing on the map: Sweden. “After the success of Mamma Mia! and Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, fans all over the world feel a claim to ABBA. Their music is iconic—Bill and I even chose ‘Fernando’ as the first dance at our wedding.” Hot. “But after lead singer Agnetha Fältskog sparked hopes that the band would get back together, the Swedish government withheld any new ABBA music from the United States to leverage us to take stronger measures against climate change.” I gasp. “I’m all about effective climate policy, Trevor, but you know how difficult it is to make progress in this country—I mean, we can’t reach net zero by 2025—and now we’re at risk of losing ABBA? You’re the Politician Without Borders, what should we do?”

I start to hyperventilate. I know that all politics is personal, but this? This hits too close to home. (I’ll never forget jamming with the boys to “Dancing Queen” on my 17th birthday.) “Well … There’s no way we can risk ABBA, so I think we need to invest in carbon capture techn—”

“YOU KNOW THAT’S TOO EXPENSIVE, TREVOR. IT’LL NEVER WORK, TREVOR.”

“We could pass a policy that holds corporate conglomerates accountable for cutting their em–”

“YOU KNOW THAT THEY DON’T LISTEN TO US, TREVOR!”

Now I’m really sweating. I can’t solve this problem. There’s too much at stake. I start to lose feeling in my body. The sides of my vision go black. I feel myself falling …

I’m jolted awake. I’m back in my Wien single. I look down and realize I’ve fallen asleep into my signed copy of alternative history novel, Rodham … again.

Why is “Dancing Queen” stuck in my head?

Negative:

If my Econ coursework has taught me anything, it’s to thrive in the uncomfortable. To find a way out when no one has before.

So, when I was in the midst of a diarrhetic episode in the International Affairs bathroom before class one day, with class-A chemical warfare fumes rising from my rectal aperture to the ceiling, and none other than Secretary Clinton strolling in, I tried to keep my calm.

I certainly did not fart loudly at the sight of my idol’s lime green pantsuit’s leg cuff in the stall door opening in surprise. The Secret Service certainly did not then kick my stall door in and escort me off the premises.

Ok, maybe I did. My previously approved background check was immediately voided, and I was removed from the class after being classified as “at best, negligent and at worst, a callous affront to human life.”

I glide across my dorm and drop into my Herman-Miller-X-Logitech-G Embody Gaming Chair®, the same one (I’m told) Obama sat in when he no-scoped bin Laden, to concoct a plan to rectify this gross miscarriage of justice. And yes, it involved rizzing up some Secret Service agents.

I caught one of the sunglass-adorned men standing outside his Cadillac off in the Wien Courtyard during class time.

“Hey there, hunk. Come here often?”

“Excuse me? I’m with the United States Secret Service. Who are you? What are your intentions here?”

“Just taking in the beautiful scenery. Nice car you’re driving.”

“Cadillac Coupe DeVille, equipped with bulletproof glass, a bombproof underbelly, two assault rifles in the trunk accessible through the backseat, a liter of the Secretary’s blood, hermetically sealed vents with a two-day supply of oxygen, an AGM-114 hellfire missile that shoots if you honk the horn twice, an in-car radio and TV system, and heated seats.”

“Wowwww, that’s really impressive. No Apple CarPlay though?”

“What is this? Are you gathering intel on Secret Service operations?”

“I just want to know how you operate. You got a permit for those guns? “

“My holstered SIG-Sauer P229 double-action pistol chambered .357 is a standard U.S. government issue, bozo.”

“Not thaaaat gun silly, I meant this one—”

I got 60% of the way to his bicep when I was thrown face-first into the cobblestone pavement. You’d think people would be a little more cordial to a future Harvard Law valedictorian.

On to Plan B: Charm one of Inside The Situation Room’s many illustrious TAs.

I found one of the Ph.D.s smoking in the IAB pit—you know, that little skylight area where Ph.D.s get their daily minimum of Vitamin D before returning underground.

“So, would you ever want to study a real politician, up close and … personal?”

“What do you mean by that, who do you know?”

“Well, you just happen to be speaking with the future President of the United States. And, with a little luck, you can look in the mirror to see the future First Lady.”

“Wellllll, I just might be interested, how about you tell me a little more later toni-”

I hear her alarm go off: It’s “By The Seaside.” I shudder.

“Sorry, I have to go back underground now. I just received my daily sunlight allotment.”

Foiled again.

My trump card was obvious: sneak into the room before class began. Unfortunately for me, the class preceding Secretary Clinton’s was Advanced Programming (AP).

I traded my Loro Piana loafers for some hideous HOKAs, and swapped my knit quarter zip for a Minecraft T-shirt reading “Creepers gonna creep.”

After I dragged my feet into AP, I set up my campsite on the floor in a middle row and was soothed to sleep with the sounds of nerds typing.

I woke up as if on command, to the sound of my idol’s voice. Something about being resourceful and never backing down. At this point, I just went back to bed. She had nothing new to offer me.

Illustration by Kendra Mosenson

Feature

Nuss and Them

A tenants’ rights attorney revisits the building, and people, he devoted much of his career to.

By Sagar Castleman

In the early 1970s, Irene Skarlatovska lived in 600 West 113th Street, a privately owned single room occupancy building (SRO) for low-income and welfare tenants. A concentration camp survivor, Skarlatovska rented a small room on the ground floor with her adult daughter, who suffered from schizophrenia. During the day, Skarlatovska cleaned other apartments in the building while her daughter stayed in the room. Their room was cluttered, and Skarlatovska’s daughter had covered the floor with multiple layers of aluminum foil.

In 1979, Columbia bought the building and hired a team of relocation specialists to oust the tenants by any means necessary. One day, a specialist entered Skarlatovska’s room, declared it a fire hazard, and, shortly afterwards, Columbia evicted them. The tenants’ lawyer took the case to court, where the head of the American Red Cross for the Northeast Region testified that if the Skarlatovskas were allowed to stay, he would personally ensure that the apartment was made safe. But the judge, known for his Columbia sympathies, ruled in favor of the university. The Skarlatovskas were thrown out. Today, their room is the Administrative Office of 600 West 113th, now known as Nuss by the hundreds of Columbia students who live there.

For me, it started with the mailboxes. One evening last April, wanting a peek at the building I’d be living in next year, I walked to Nuss for the first time. Upon entering, I immediately noticed a grid of gleaming golden mailboxes behind the security guard. Thinking of the Mail Center, I asked the security guard if the mailboxes were for students. In reply, he told me a story.

The guard said that before Columbia bought Nuss, it was an apartment building. When Columbia took over, they said that all tenants had to leave, and the tenants sued. “Some of them won, some of them lost,” the guard told me. “The ones who won stayed. And some of them are still here.”

Walking back up Broadway, the story of the old tenants stuck with me. I imagined what it would be like to be an ordinary adult living in a college dormitory, surrounded by undergrads moving in and out every year. I wondered if the tenants hated Columbia, who had tried its hardest to force them out and who was now their landlord. I wondered if they had any relationships with the students who surrounded them and yet were always changing, if they felt a little bit like an old teacher who has had so many students over the years that they all blur together. I wondered if the remaining tenants had gravitated towards each other once they realized that they and the physical building were their only constants in a sea of change.

These questions resurfaced when I returned to the city in September and moved into Nuss. In the elevator one morning, I found myself standing next to a short elderly man in a gray hoodie. I considered saying hello, but he was frowning deeply and wearing a tangled pair of wired earbuds. I chickened out.

But my curiosity persisted, so I asked the security guard on shift if I could talk to any of the old tenants. She said that most of the tenants had died, and the ones who were still here were very old, but she suggested I try to talk to a man named Mr. Ben. She gave me his room number.

Later that day, I put on a collared shirt, walked down a few flights of stairs, and entered an ordinary-looking Nuss suite with a shared bathroom and kitchen. I knocked on the only door without a name tag. It opened, and inside was a dorm-sized room covered with clothes, medicine bottles, and papers. It smelled of age. A TV was on, and, against one wall, was a narrow green couch. In front of me stood a small older man who smiled and introduced himself as Benjamin Oyogho.

Oyogho moved into Nuss in 1974, back when it was an SRO. At the beginning, when Columbia had tried to force him and the other tenants out, Oyogho had been upset. But after winning his case, his vexation with the University waned. “As long as you pay your rent, they’re maintaining the building,” he told me. According to Oyogho, the building is better maintained now than when it was individually owned because of Columbia's responsibility to their young students’ parents. “We benefit from the attention Columbia, not necessarily gives to us as the old tenants, but to the students,” he explained.

Although 600 West 113th has grown steadily nicer with each of Columbia’s many renovations, Oyogho has remained here for nearly fifty years not because of the building itself, but because of its location. He appreciates the ease of the transportation, the convenience of the shops, and the steady security and police presence in the area. Despite Columbia’s pressures on him to leave, Oyogho continues living in what he deems the best neighborhood in New York.

Oyogho no longer knows most of his neighbors—most of them have either died or moved out. The only tenant he still knows well is currently sick and bedridden, and Oyogho didn’t think it would be ethical to give me his room number. He also wasn’t close with the students who moved in and out of his suite every year. “Say, ‘hello,’ ‘hello,’ if you want, otherwise you get in the elevator and go about your business.”

Chatting with Oyogho answered some of my questions, but I still had more. So, I started digging through archives of local newspapers from the late ’70s and early ’80s, when Columbia’s landlordship was constantly in the news. A New York Times article from 1979 about two deaths due to masonry falling off of Columbia-owned buildings reported that the tenants of 600 West 113th “[said] they were being abused and harassed… The[y] now insist that they will resist Columbia’s planned effort to relocate them. Columbia denies any responsibility for the tenants’ alleged harassment.”

I first found mention of tenant attorney Kenneth Schaeffer, CC ’76, in a Columbia Spectator article from 1987, and then again in a Spec article in 1980, where he was referred to as the coordinator of the Morningside Tenants Federation. In 1985, a columnist for The Daily News called him “the people’s lawyer on Morningside Heights.”

I emailed Schaeffer, and we met a few days later at the Hungarian Pastry Shop. With a New York accent and tufts of white hair sticking up, Schaeffer was warm and grandfatherly. As he sat down, he recounted how he had been a dishwasher at Hungarian when he went to Columbia in the early ’70s. A democratic Marxist who remembered watching Eleanor Roosevelt speak when he was 9, Schaeffer emphasized the political nature of his life’s work as a tenant lawyer.

Before Columbia bought 600 West 113th, its apartments were rent controlled, and under New York state law, rent-controlled tenants couldn’t be evicted without reason. Since Columbia couldn’t legally force the tenants out, it resorted to nastier tactics like cutting the heat, turning off hot water, and, most egregiously, repeatedly draining the rooftop water tower, causing rooms to flood and ceilings to collapse. Schaeffer described this as “harassment with the intent of forcing them out,” and, under Columbia’s pressure, many of the tenants left. By the time Schaeffer was assigned to represent the tenants at the beginning of 1980, about half of the building was empty, and the University was trying to consolidate the remaining tenants into the seventh and eighth floors so they, as Schaeffer put it, “wouldn’t mix with the pure blue-blooded Columbia students.” Many of the tenants who stayed went on rent strike. Columbia sued those tenants, arguing that they should be evicted for not paying their rent.